Hard Questions

He sure knew how to ask them. This guy was a thinker. He liked to project an air of confidence. And he seemed to like a good debate and an intellectual challenge.

Rich* had an extensive background in movement and fitness based practices. He taught fitness classes at a studio I used to teach FeldenkraisⓇ lessons at.

One day, finding me waiting in the reception area for my next client, Rich asked me about the work I did as a Feldenkrais practitioner. In particular, he wanted to know what some of the distinguishing features of the Feldenkrais MethodⓇ were…

Somewhere along the line I shared something about how Feldenkrais practitioners recognize the importance of the skeleton, seeing as its what holds us up. I probably made some comment about how we often spend too much time worrying about what muscles we need to use when what we really needed to do was clarify our image of our own skeleton, and how it needed to move through space to accomplish our tasks.

We didn’t get very far in our conversation since my client arrived and I had to go off to work.

A couple weeks later another of the instructors at the studio wanted to engage in a similar conversation. She had been talking to Rich about the discussion I’d had with him.

She and Rich thought my ideas about the importance of the skeleton just didn’t make sense. They were certain it was the muscles that hold us up.

Rich had come up with an analogy to explain why what I’d said didn’t make sense. His analogy was of a slurpee (if you’re not from Winnipeg and haven’t been to a 7-Eleven convenience store, a slurpee is basically a slushee).

From his way of thinking, the straw represents the the skeleton and the slurpee represents the muscles. If there were no slurpee, the straw would fall over.

I pointed out that there were a couple of problems with this analogy.

First, the straw could conceivably stay upright all on its own. Seeing as its base of support is incredibly small and its centre of mass is very high in comparison to its base of support, it’d be damn hard to balance in an upright position. But it could be done, at least theoretically.

Secondly, and far more importantly, Rich and his colleague completely overlooked what actually represented the skeleton in his analogy — the cup!

Without the cup, the slurpee wouldn’t be holding up much of anything.

In this analogy, the ‘cup as skeleton’ would be an exoskeleton. Insects are examples of critters that have exoskeletons. Instead of having bones inside them to counteract the pull of gravity, they have a rigid outer layer on which their muscles and connective tissues are attached. But its still a skeleton none the less.

Let me be clear that I think Rich was making an important point.

The skeleton does not act alone in holding us up.

The skeleton is a part of the complex, whole, unity that is you or me. The fascia (connective tissue) plays a very significant role in organizing the skeleton as do the muscles and every other bit of us, and the environment, not the least of which includes the ground we stand on and the ever present force of gravity we live in.

Still, crucially, tissues such as muscles would not be able to “hold us up” in the field of gravity, or move us very well were it not for the skeleton.

The Oh So Taken for Granted and Under Appreciated Skeleton

Feldenkrais practitioners often speak of “skeletal organization”.

There are a couple of key ways to describe what is meant by “skeletal organization”. They have to do with how loads are transferred from one bone to the next at our joints.

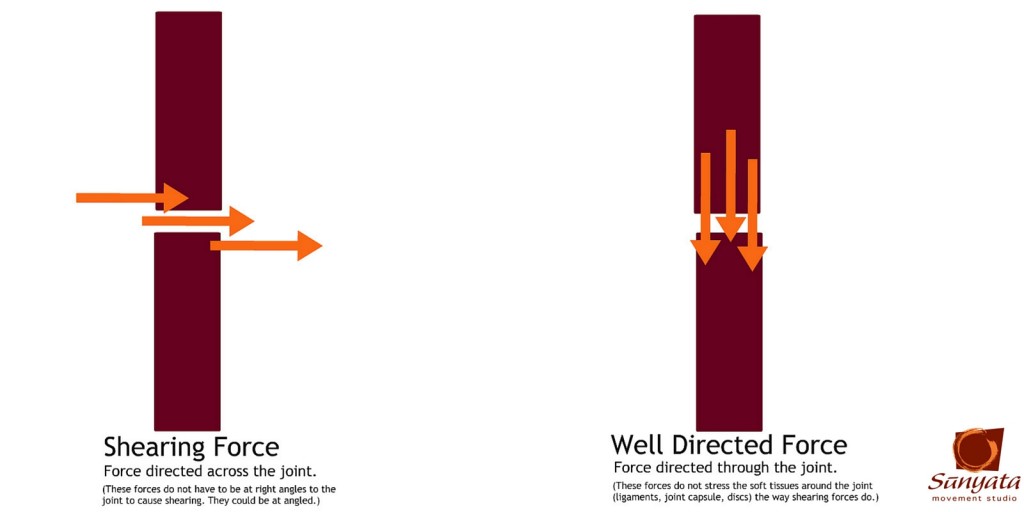

1. When you’re skeletally organized, you’re transferring load through your joints, not across your joints.

The ‘load’ is the weight of your own body, plus the weight of anything you’re lifting or carrying, or you pushing or pulling something to move it or yourself etc.

What you want is to transfer any force through your skeleton so that the force/load keeps being transferred on to the next bone, and the next, and the next…without undue stress on the soft tissues that help keep the joint intact.

This way, no one joint is forced to take the lion’s share of the load. And more than this, you transfer the force into the environment whether that be, a door you’re opening, a shovel you’re pushing into the soil, a turkey you’re lifting out of the oven, a ball you’re throwing, a bike you’re peddling….and in particular, the ground you are making contact with.

When poorly organized, you don’t transfer the force of gravity or the forces you generate within yourself through your skeleton and through your joints. Instead, you’ll cause shearing forces across your joints.

When you do this you:

- put yourself at risk of injury because you put an awful lot of stress on the soft tissues — ligaments, discs, joint capsules, muscles, fascial tissues…

- use more energy than necessary for the task at hand — you waste energy

- move less skillful because there are movements you’re doing to protect your joints and/or are working in opposition to the movement you want to carry out

- are able to generate far less power because you are contradicting your own actions with protective and/or superfluous muscular contraction

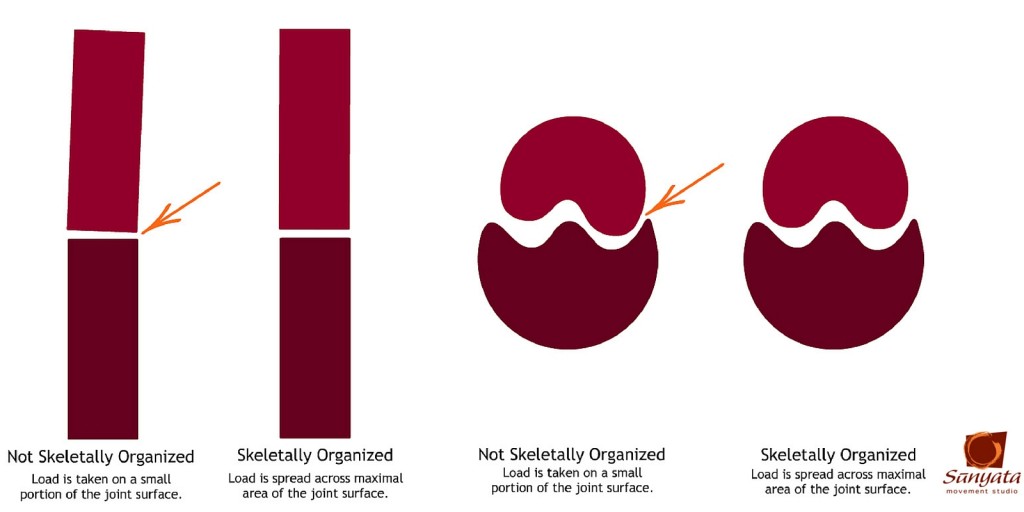

2. When you’re skeletally organized the maximum joint surface at the interface of two bones is utilized. Perhaps better put, there is an even-ness of stress all around and through the joint.

By distributing the load at each joint over and around its entire surface area/interface, no one, small area, no one side of a joint and its tissues is overly stressed and worn.

This allows you to:

- exert all your efforts towards the task at hand

- distribute the forces applied throughout your entire system

- transfer forces to the ground instead of your own tissues

- move with less effort

- adapt and change the direction of your movements easily and effortlessly as needed

You move with efficiency, power and grace.

The Connection Between the Skeleton and the Brain

Here’s a fact that might surprise you (seeing as the world tends to be so muscle-centric 😉 ).

There is a part of your brain that is selective for the arc of your bones as they move through space — as opposed to the muscles that move those bones.**

Again, so as not to be misunderstood, I feel its important to say that I believe we are and function as a “complex system”. When I say that, I don’t mean we’re complicated (although, some people certainly are 😉 ). What I mean is that we function as unified systems, that are more than the sum of our parts.

So — although I’m highlighting the skeleton and am inviting you to consider attending to your skeleton more, I’m not saying that the skeleton acts devoid of fascia, muscles, your brain, the rest of you and the environment.

In fact, the whole notion of “stacking our bones” as though we are stacking building blocks is a very poor way of thinking of upright posture. Why? Because in actuality, our bones are “floating” in a complex matrix of fascia, muscle and extracellular matrix. We function more as a tensegrity structure.***

But I digress. Tensegrity*** can be for another blog post.

Let’s get back to skeletal organization…

When you organize yourself skeletally, there is an evenness of stimulation of all the neuro-receptors around each joint. When forces are transmitted through a joint with this evenness all around, it’s as though your brain recognizes, “Oh, I’m going to be taking a load here and I’ll prepare for that by activating the anti-gravity musculature.”

This anti-gravity muscular system is what provides deep, functional stability for your joints in preparation to take increasing load or in other words, do more work.

Some of the characteristics of this anti-gravity muscular system are:

- tone in these muscle fibres ramps up slowly

- contractions are not powerful

- extremely resistant to fatigue (it can be engaged all day long without tiring)

- minimal sensation of any muscular contraction (hence the feeling of lightness and sometimes even the sensation of floating)

- primarily controlled by reflexive mechanisms in parts of the brain much deeper than than the voluntary motor cortex!

I’m going to reiterate a couple of points above because they are super important to this discussion of finding the power and strength to move with ease and grace…

The last point is particularly interesting. The anti-gravity mechanism that provides deep, functional stability comes in large part from aspects of your brain that are not in the conscious, voluntary parts of your brain.

Instead, the parts of the brain that control this anti-gravity mechanism come from deeper areas (thalamus, brainstem) and the control is primarily an unconscious process.****

Get this! When the fore-brain, or cerebrum (thinking, planning part of the brain from which conscious movements are organized) is severed from the rest of an animal’s brain (decerebration), the animal will still be able maintain upright standing all on its own once placed there. It will have more than sufficient tone in its anti-gravity muscles and does not need the voluntary motor cortex or the primary sensory cortex!****

Another super interesting point noted above…

When those deep parts of the brain fire up those anti-gravity muscle fibres that provide that lovely stability that results in “skeletal organization” — you don’t really feel the muscular engagement!

What you feel is an incredible lightness and ease. Sitting upright and standing feel effortless.

The feeling is more of an absence of effort!

You might be asking some important questions at this point like:

- If this is an unconscious, reflexive process that happens without even having a connected fore-brain/cerebrum, why aren’t we all standing and moving effortlessly all the time?

- If my standing doesn’t feel effortless and this skeletal organization isn’t controlled by my conscious processes, then how the heck can I change the way I’m organizing myself?

- If I don’t feel the muscular engagement of these deep, stabilizing, anti-gravity muscle fibres engaging, then what feedback do I use to help me know if I’m doing what I need to have this effortless, floating quality?

Here’s What You Can Do To Find the Power & Strength to Move with Grace & Ease

Let’s look at those questions one at a time…

We aren’t all standing and moving effortlessly all the time because our fore-brain/cerebrum is still intact. (At least yours and mine are seeing as I’m writing this, and you’re reading this 😉 ).

Your fore-brain actually inhibits the excess tone and rigidity in the anti-gravity muscles that would take place if only your lower brain centres were functioning.

Your fore-brain modulates the automatic, reflexive actions of your mid-brain.

The thing is, that since we function as a unity and our thinking is as much a part of movements through the world as the mechanical motions of our skeleton through space, and since our habitual actions depend on learning and past experience, we can do an awful lot to interfere with the natural functioning of the anti-gravity system and smooth, easy, effortless motion.

In other words, its pretty easy to develop self-limiting habits of thought and motion. Some of these start very early in life. Others we develop due to trauma, injury, crazy ideas we have about ourselves, the world and how things should be…like the self-limiting beliefs I wrote about here and here.

Sometimes, as a protective mechanism, we drop our anti-gravity tone. This may serve us in the very short term, but can become a real problem in the long term.

Its important to remember that its our forebrain/cerebrum that inhibits the spontaneous, reflexive engagement of the muscle fibres that make up our anti-gravity mechanism.

This leads into my answering the second question: If this lovely anti-gravity mechanism isn’t controlled by conscious processes, how can I make a difference in myself?

The difference you can make is in removing the ways your fore-brain is interfering with the natural mechanisms of your anti-gravity neuro-muscular system.

In so many ways, its about letting go of the conscious efforting; about releasing the self-limiting habits that interfere with easy upright organization. We need to lift the dampening effect that our conscious mind is having on the anti-gravity mechanism. It’s like Morpheus says to Neo in the sci-fi movie The Matrix, “…free your mind…”

Its about learning to move with less and less superfluous, unnecessary work. Its about letting your natural responses to gravity and load emerge uninhibited once again.

And in turn, this leads right into the answer for the third question: If I don’t feel the muscular engagement of the anti-gravity muscles, what feedback do I use?

The feeling of effortlessness!

Do everything you want to do with less effort!

I wrote about this in a short, free eBook you can claim here: Overcome Nagging Pain & Injury: 3 Keys to Powerful, Flowing, Natural Movement Without Pain.

In it I clarify what I mean by doing everything you want to do with less effort. Its about looking for a feeling of effortlessness no matter how much force or power you need to exert for the task at hand.

Other things you can do to find this effortlessness:

- learn to transfer forces to the ground or your supporting surface whatever that is

- exploring movements that allow you to use your bones more clearly to transfer forces through your system

- have an even-ness of pressure through your joint surfaces and all around your joints…

Here’s A Tiny Movement Awareness Experiment to Help You to Find The Source of Your Power and Grace: Your Skeleton and Anti-Gravity System

Lie on your back on the floor with your feet flat against a wall spread about hip width apart and so that your knees are directly in line with your ankles:

Very, very gently, push through your feet and notice how you tend to organize this movement, and release the pushing. Do this many times and…

- Notice what parts of your feet press into the wall more clearly

- Do any parts lift away from the wall?

Continue to push and release very gently, many times. Begin to organize the movement so you feel an even-ness of pressure throughout your whole foot, in particular your heels…

- What do you feel at your ankles?

- Can you imagine that the force through you ankles is evenly distributed over the entire surface of your ankle bones? Not just the front or the back, or the outside or the inside….

- How do you organize the movement when looking for this even-ness of pressure?

Continue to do the push and release very gently and notice your knees…Push and release slowly and gently….

- Is the pressure through your knees more to the outside or inside of the knee joints?

- Is it the same on both knees?

- Can you organize the pressing so the sensations of pressure are evenly distributed throughout the surface of your knees?

Continue and feel…

- Does this movement seem to go through your entire skeleton?

- If not, how far through you do you feel its effect?

- Could you allow the movement to resonate all the way to your head? As though the smallest, gentlest pushing into the wall is a force that moves your entire self as though you might slide yourself ever so slightly away from the wall

Can you do all this while breathing with the greatest of ease, simply and spontaneously?

After exploring this gently for 5 to 10 minutes, notice what standing upright feels like.

Finding your skeletal organization and taking advantage of the natural anti-gravity mechanism will help you find the power and strength to move with grace and ease.

I will be uploading a short video to the Free Content Library that will guide you through this movement experiment and more. The ideas in this post and in the short video will blend well with those in the blog post: Got Back Pain? Why Strength and Flexibility Don’t Cut It and What To Do About It

The Free Content Library is a constantly growing library of resources to help you move and live better.

To claim your free membership, just click here.

* Name and some other details have been changed to protect the persons identity.

** Neurophsysiology texts such as: Principles of Neuroscience by Kandel and Schwartz go into extreme detail about this.

*** Tensegrity is defined in Wikipaedia as “tensional integrity or floating compression”.

Another great source of information regarding tensegrity related to living structures (biotensegrity): Levin, Stephen, “Tensegrity, The New Biomechanics”; Textbook of Musculoskeletal Medicine,

And at the website: biotensegrity.com

**** Many neurophysiology texts explain this, including Principles of Neuroscience by Kandel and Schwartz.

Moshe Feldenkrais writes about this in his book, Body & Mature Behavior: A Study of Anxiety, Sex, Gravitation & Learning.

Other easily accessible online sources regarding the neurology of the anti-gravity mechanism can be found at the following:

http://cw.tandf.co.uk/neurophysiology/sample-material/Neurophysiology-5E_Chapter-11.pdf

http://www.neurorestart.co.uk/postural-reflexes/

This is well worth rereading periodically. I always learn something new. The refresh is invaluable.

Wonderful! I’m glad you found it helpful.