Effortless Effort The Feldenkrais Way

This is a an edited reprint of a previous post about one of Feldenkrais’ four elements of quality movement: the absence of effort.

Feldenkrais spent a great deal of time making it clear that…

“….posture relates to action, and not to the maintenance of any given position. Acture would perhaps be a better word for it.”*

He pointed out that the image of ideal posture shown in medical textbooks or on those medical charts with a plumb line overlain on the skeleton is a pretty crazy way to look at what “proper” posture is.

For starters, such an image doesn’t take into consideration the genetic situation of a person’s anatomy. Not a single one of us is born “perfectly” with every bone shaped exactly so. And some are born with significant alternatives to the so-called “ideal”, like those with congenital scoliosis. Does this mean these people can’t have good posture/acture? Absolutely not!

Neither does it take into consideration that we’re not simply skeletons. We are each a unity, a unity that has a brain —- a brain that learns.

Each of us has a unique history of injuries, traumas, challenges and successes that quite literally, shape us.

It took you and me an average of about a year or so to learn to walk. In that process, we each came to learn to walk rather differently…

I went from a wheeled walker thingy to walking super early with very little crawling. You, meanwhile, might have done an awful lot of “side sit scooching” with a preference to side sit right and then up to walking with very little crawling either, for example.

Heck, I have a nephew who was a log roller. Really! If he wanted to get across the living room floor to get to something that interested him, he would lay down on the floor, log roll over, then pop up into sitting and play with whatever it was that had captured his interest.

Others spend many months crawling everywhere and don’t start walking until after a year.

All these variations shape us in unique ways. So to have one image of ideal posture is not useful.

Another very important consideration is that this “ideal, text book posture” might hint at a general direction for all of us to move towards, but only for upright standing!

Honestly, how often is this posture actually something you do? How truly functional is it? In other words, there isn’t much one can do in such a posture. It’s static and doesn’t really relate to a living, moving, active being.

Seriously, what is good posture when:

- putting on your socks

- sitting for a meal

- pulling a roast out of the oven

- planning a party

- swimming the breast stoke

- deciding on the direction for your business

- when skiing or water-skiing

- playing the piano

- solving a calculus problem

- riding a horse

- having sex

Not a single one of these examples looks anything like what that medical picture looks like. And yet you can probably recognize the difference between poorer posturer/acture and better posture/acture.

What Makes for Good Acture (Posture)?

Feldenkrais suggests there are two ways of considering the appropriateness of acture:

- Whether or not the acture accomplishes the action to be achieved

- The way in which the action is accomplished

The first criterium listed above isn’t quite enough to determine whether something has been done well or not. It isn’t irrelevant, but you could accomplish your goal incredibly unskillfully and perhaps with significant negative consequences. If that were the case, would the acture have been “good” acture?

I don’t think so, and neither did Feldenkrais.

To make this clear he pointed out that it’s not that a person paints but how she paints; it’s not that you play the piano, but how you play that determines whether or not you’re acting well. It’s the way the action is accomplished.

In his book, The Potent Self, Feldenkrais wrote several times that the distinguishing feature of healthy, potent, mature behaviour is that it is free of compulsion:

As far as potent, healthy behaviour goes, nothing is more important than the degree of internal compulsion with which we act. The important things will take care of themselves; we always have to eat, think and learn, have children and die — no matter what we may believe. The way we do these things is the cardinal point of healthy or unsatisfactory behaviour.

The shortcomings of many educators and methods are largely due to neglecting to recognize the process of maturing in its entirety. Often, therefore, remedial action is directed to the act, or the object of the act, and not to the way it is performed.”

Moshe Feldenkrais, The Potent Self

When considering the appropriateness of acture by the way the action is accomplished, Feldenkrais noted that, “…most people make absurdly bad use of themselves.”*

He states that,

“Correct posture is a matter of emotional growth and learning. It is not acquired by simple exercising or by repetition of the desired act or attitude.”*

So what do we have to learn?

Feldenkrais’ Elements of Quality Movement

“In any co-ordinated, well-learned action — such as thinking, speaking, eating, breathing, solving problems, drawing, or fighting — we can distinguish certain features or recognize the following sensations:

1. The Absence of Effort

2. The Absence of Resistance

3. The Presence of Reversibility

4. Free Breathing”*

Today we’ll take a closer look at the first: The Absence of Effort.

“In good action, the sensation of effort is absent no matter what the actual expenditure of energy is.

Much of our action is so poor that this assertion sounds utterly preposterous.”*

But take a moment to consider why it’s so wonderful to watch the most beautifully graceful dancers, paragons in sport, or healthy animals moving in the wild and you realize that it’s the un-conflicted motion, the absence of the appearance of effort, the utter grace that captivates us.

Think of anything you yourself do well, skillfully and effortlessly. You’ll notice that, as Feldenkrais put it, “…the sensation of effort is the subjective feeling of wasted movement.”*

Go ahead — think of anything you do really well and easily. Imagine yourself doing it. Now imagine doing it the way a beginner would do that very same thing, or how you did it when you were a beginner…

If you actually imagine the sensations you’d have, or in fact do it just as a beginner would, you’ll quickly notice how much wasted effort there is!

He goes on to say that…

“All inefficient action is accompanied by this sensation [of effort]; it is a sign of incompetence. When carefully analyzed it is always possible to show convincingly that the sensation of effort is due to other actions being enacted besides the one intended.”*

Don’t get hung up on the word “incompetent”. It is not a judgment regarding your or my quality or value as an individual. It simply points out that we are not yet skilled at something — not yet competent.

And, he puts it another way…

“It is very important to realize that incompetence does not mean lack of the essential action for achieving the end, but consists largely in enacting unnecessary parasitic acts.”*

It continues to amaze me just how much we interfere with our own natural intelligence. I’d venture to say that the majority of what we need to do to learn to move spontaneously, potently and skillfully is notice all the ways we’re adding more than required, and STOP doing all that extra wasteful work.

It’s incredible how often clients will say something like, “But I don’t know what I’m doing to get this great feeling.”

This comes up when I help them feel that they can move with so much more ease and power then they had been with their previous habits. They certainly feel the difference. They are producing the difference between the two ways quite beautifully all on their own. So what is it that they don’t know?

The answer to that could be an entire series of blog posts in and of itself as the notion of “awareness” as Feldenkrais spoke of it is a pretty deep topic in my mind.

But the point to be made here is that all too often it isn’t so much about what they are “doing” to have the new ease and power. It’s about what they stopped doing. They removed the tendency to limit their natural, flowing movement.

In the blog post: How to Find the Strength & Power to Move with Grace & Ease, Even if You Have a Back Injury I attempt to describe some of the neurology that helps explain this. In it, I wrote about the anti-gravity mechanism and how it’s controlled by parts of our brain much deeper than our forebrain. This deep area does not require our voluntary motor cortex to engage our anti-gravity musculature.

In other words, we don’t have to work so hard to have “good posture”. It’s more about working intelligently, efficiently, and naturally.

Instead of allowing our system to work efficiently and effortlessly, too often we interfere and manipulate ourselves with such compulsivity, we begin to think it’s necessary and normal.

In reality, we are far more capable than we often give ourselves credit for.

But how do we go about stopping those unnecessary elements? We often don’t even recognize how much extra, wasted effort we put into things. And because we are so darn used to the sensations, we think they’re normal.

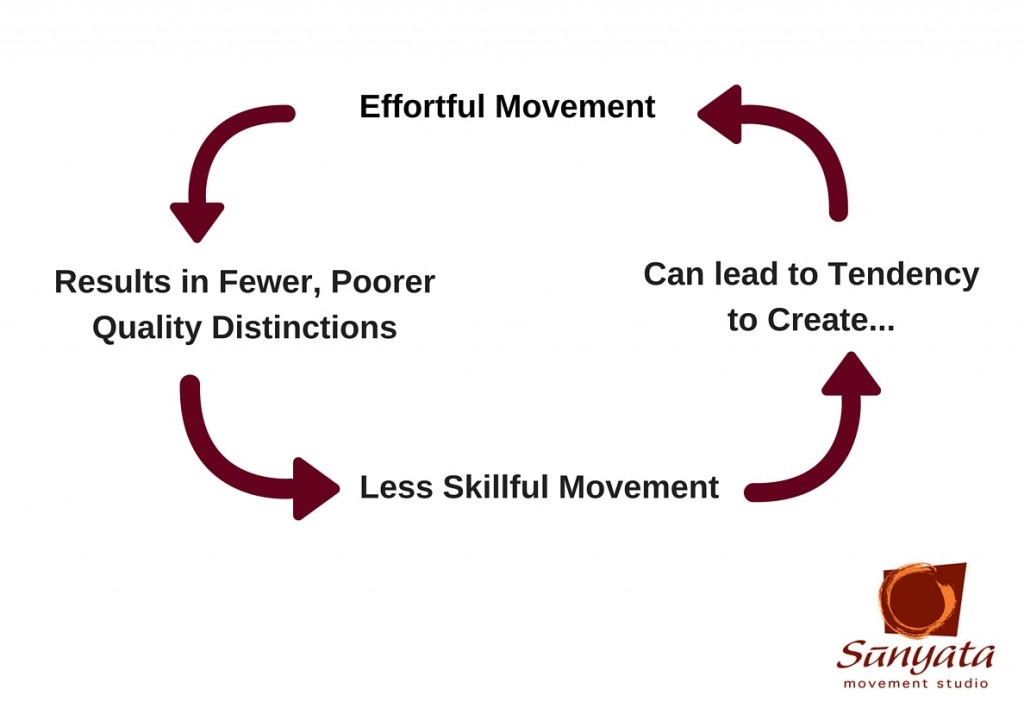

To make things seem even worse, as pointed out in this blog post, because of all the excess effort, we’ve limited our ability to develop our library of distinctions. And it’s these distinctions that are necessary to learn to do anything truly masterfully…

It’s a bit of a vicious circle….

So maybe this seems pretty bad. But here’s a worthwhile little spin…

You can cut yourself some slack with regards to moving inefficiently. How could you move better than you are given that you haven’t known anything different?

Every single one of us has blind spots. Things we do that we just don’t know we’re doing. Places in ourselves that are obscure and unclear.

What To Do

The first thing to do is recognize that you’re not flawed, bad or anything less than perfect just because your actions are laden with compulsivity. It just means you’re human! ?

The more you can accept your ‘incompetence’ as simply a part of the process of maturing, growing, and becoming more skillful, the more quickly, easily and enjoyably you’ll learn to become more ‘competent’.

In other words, practice dropping any critical, judgmental, harsh voice when uncovering your unskillful ways of moving and acting in the world.

I l-o-v-e-d this quote from Feldenkrais when I came across it:

“Everyone is functioning perfectly — given their perception of choices.”

It reminds me of the zen saying:

“You are perfect as you are. And — there’s room for improvement.”

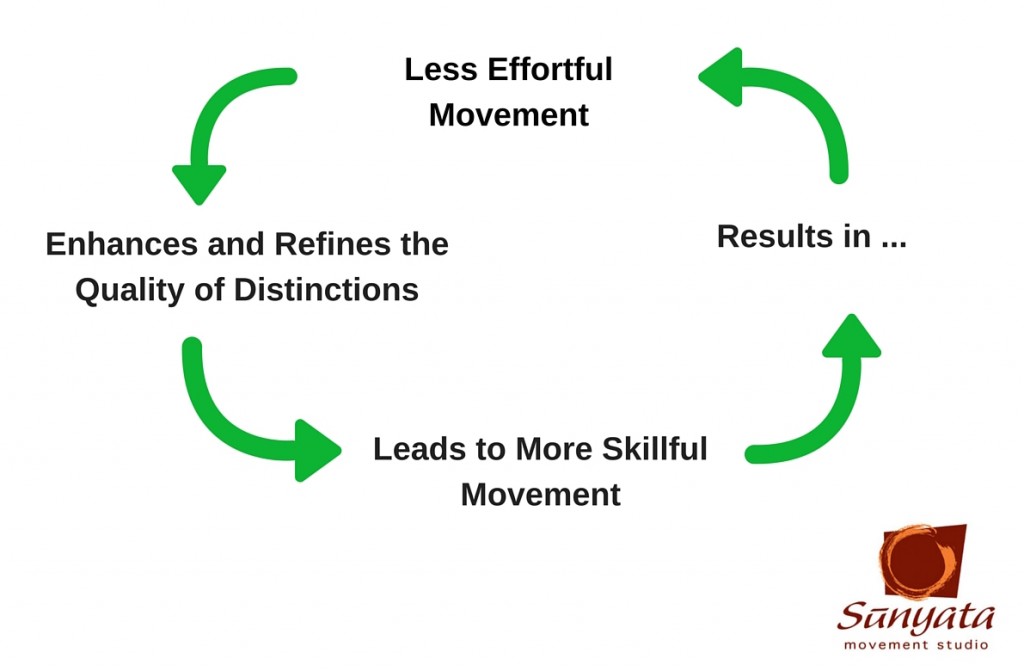

Now, with a non-judgemental attitude, as often as you can, whenever it makes sense, shift your attention away from the goal of your action, to the means by which you do the action. Seek to move with less effort, and keep paying attention…

In other words, be present to your experience as you are experiencing it, with a gentle, attentive, open, inquisitive, curious state of mind while decreasing all the extra, wasted activity doing whatever you find yourself doing.

The Payoff to Moving With Less Effort is Incredible

Not only does it allow you to make more distinctions which makes learning better movement faster and easier, but you immediately begin to improve the way you organize/coordinate yourself…

You can’t do the thing you are currently doing with less effort without automatically improving your co-ordination. You can’t lift the 50-pound bag of bird seed into your car with less effort without improving your organization. The bag still weighs 50 lbs. So what’s changed? You.

Then there are the benefits of putting less strain on your system; less wear and tear. There’s also the benefit of having more energy and living with more vitality.

And of course, there is also the wonderful experience of being more present to your life…

Such a simple thing has such a profound impact.

To help you notice where you add unnecessary effort while moving through the world, here are examples of some of the most common indications of excessive activity you could listen for:

- the tiniest interference or interruption in breathing

- the smallest increased tension in your jaw, tongue or throat

- the furrowing of your brow

- and the whole gamut of efforting to have so-called “good posture”

- holding in your stomach

- holding up your chest

- tucking your chin in

- pulling your shoulders down & back

- and so on and so forth

What might it feel like to stand, walk, talk, think, do with elegance, grace, vivaciousness, presence, freedom and natural, flowing movement?

Explore, play, notice, learn, be curious about yourself —— all without judgment!

And remember…

“Maturity is not a state reached with age or experience — it is a process that goes on until death in all evolving and creative people.”*

~Moshe Feldenkrais

If you haven’t joined my FREE Content Library yet, sign-up now!

In it, you’ll find free Awareness Through MovementⓇ lessons, and educational videos to help you:

- grow your library of distinctions

- find more natural, flowing movement with less effort

- learn to learn better, faster and easier

- enhance and clarify your self-image

- be more fully you!

This Free Content Library will continue to grow on a regular basis. And you’ll have access to everything there for as long as you’re a member — completely free.

*The Potent Self by Moshe Feldenkrais

Leave a Reply